OSD 192: Safety at scale

This story came out of Miami on Wednesday:

The U.S. Customs and Border Protection agent killed at a West Miami-Dade gun range on Wednesday was accidentally shot by a fellow agent, Miami-Dade police said on Thursday.

Multiple law enforcement sources told the Miami Herald that it happened during a role-playing scenario in which one of them was trying to subdue a bad guy. The sources said the agent who shot Arias had accidentally replaced his training pistol with his handgun, which carried live ammunition. How that happened wasn’t immediately clear.

– “Fed agent killed at gun range was shot by fellow agent in role-play scenario, sources say”

Similar things have happened in the past. A retired librarian was shot dead in 2016 by a police officer running a self-defense class, after the officer incorrectly thought he was using blanks. And obviously, the vast majority of accidental shootings take place outside of a police training context. There are a little over 400 accidental shooting deaths per year in the US.

You don’t have perfect control over whether you end up on the receiving end of an accidental shooting. But you do have near-perfect control over whether you cause one. What’s the way to do better here?

Well, look at this chart of car crash deaths in the US over time:

Deaths per person are down about 60% from their peak. Deaths per vehicle-mile traveled are down more than 90%.

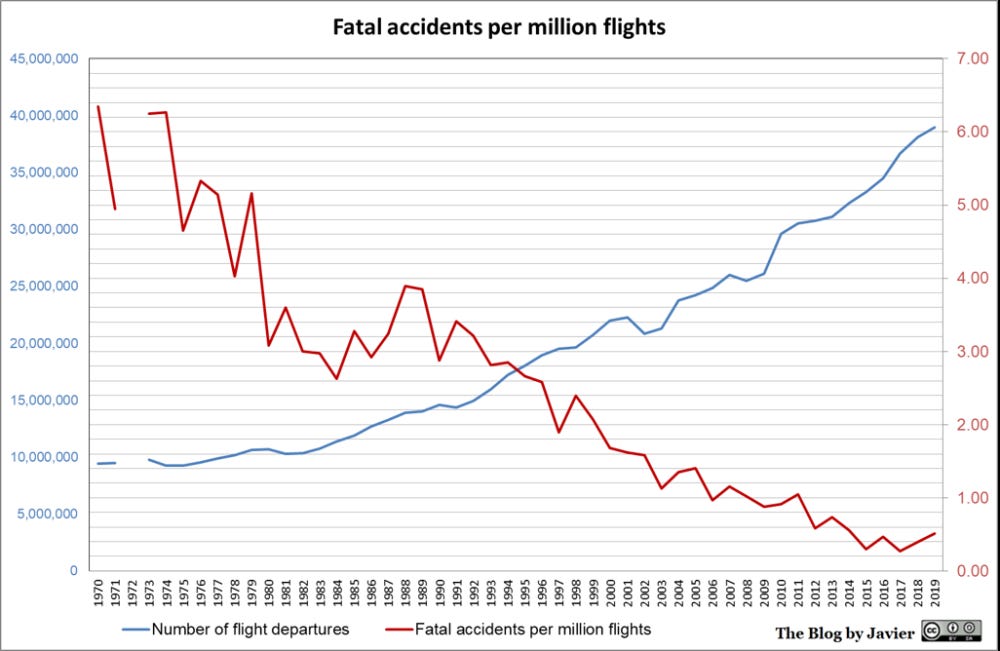

Pretty good. Now check out this chart of airline deaths per flight:

Down >90%.

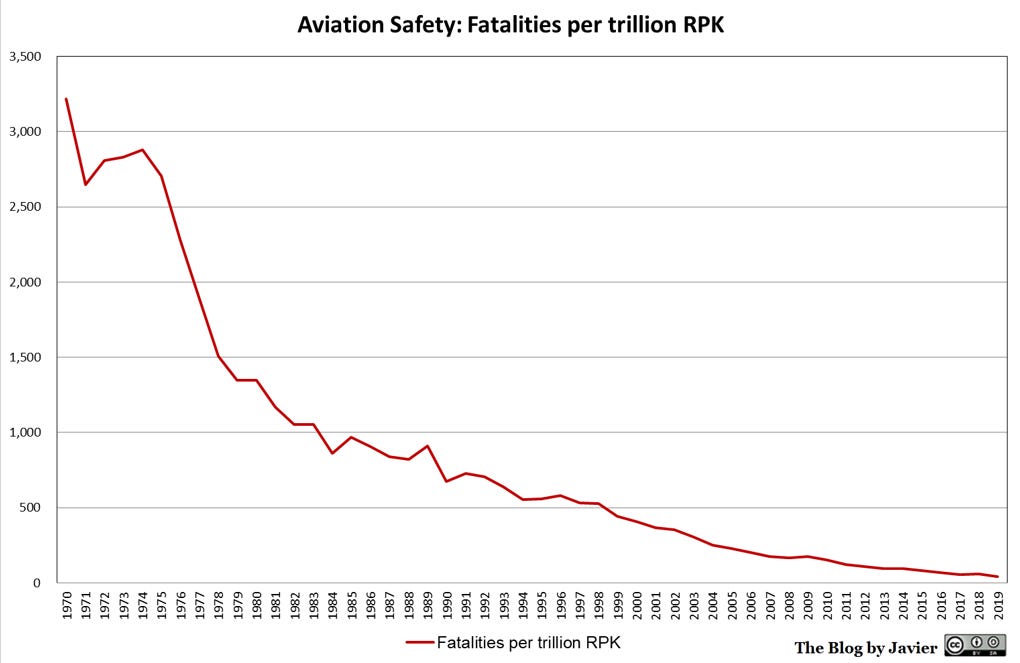

And deaths per trillion revenue-passenger kilometer:

Down about 97%.

You drive results like that by thinking at scale. Think about a dry fire procedure. Or a holstering procedure. Or a drawstroke. It’ll work safely ten out of ten times. And probably a hundred out of a hundred. Maybe a thousand out of a thousand. But those are human-scale numbers. Our monkey brains deal in those. We don’t deal in millions, but gun safety does. Is your holstering procedure reliable enough to work safely one million out of one million times? Not a single violation in all those reps?

On average, two million flights need to take off before there’s a single death. And the vast majority of those are in “general aviation”, i.e. every rando with a Cessna. The major U.S. carriers had zero fatalities in 2020, on 4,519,110 departures. In fact since 2002, the major carriers have averaged one fatal accident per 18 million departures. Since 2010 they have had a total of two deaths. (Data here.)

Gun rights are winning. We’re partway through making tens of millions of new gun owners. That means we need to think at scale.

There’s a legendary engineer at Amazon named James Hamilton who writes a good blog of musings and learnings from his career. He wrote a post in 2017 titled “At scale, rare events aren’t rare”:

In normal operation the utility power feeding a data center flows in from the mid-voltage transformers through the switch gear and then to the uninterruptible power supplies which eventually feeds the critical load (servers, storage, and networking equipment). In normal operation, the switch gear is just monitoring power quality.

If the utility power goes outside of acceptable quality parameters or simply fails, the switch gear waits a few seconds since, in the vast majority of the cases, the power will return before further action needs to be taken. If the power does not return after a predetermined number of seconds (usually less than 10), the switch gear will signal the backup generators to start. The generators start, run up to operating RPM, and are usually given a very short period to stabilize. Once the generator power is within acceptable parameters, the load is switched to the generator. During the few seconds required to switch to generator power, the UPS has been holding the critical load and the switch to generators is transparent. When the utility power returns and is stable, the load is switched back to utility and the generators are brought back down.

The utility failure sequence described above happens correctly almost every time. In fact, it occurs exactly as designed so frequently that most facilities will never see the fault mode we are looking at today. The rare failure mode that can cost $100m looks like this: when the utility power fails, the switch gear detects a voltage anomaly sufficiently large to indicate a high probability of a ground fault within the data center. A generator brought online into a direct short could be damaged. With expensive equipment possibly at risk, the switch gear locks out the generator. Five to ten minutes after that decision, the UPS will discharge and row after row of servers will start blinking out.

This same fault mode caused the 34-minute outage at the 2012 Super Bowl: The Power Failure Seen Around the World.

When you’re thinking about gun safety, think at this kind of scale. If your procedure can’t run millions of reps between failures, keep making it better.

This week’s links

“My Sig P320 fired in the holster and tried to shoot me”

Speaking of designs that are unsafe at scale…. Sig is starting to permanently harm itself by not addressing the safety rumors about the P320.

Canada’s handgun ban took effect on Friday

Current possessors are grandfathered, but there will henceforth be effectively no new legal handgun owners in Canada.

Steven Gutowski joins CNN as an analyst

Couldn’t have a better journalist on the gun beat.

Federal judge strikes down New York’s ban on carry in places of worship

Bruen keeping judges busy.

This guy turned his eye into a flashlight

This has nothing to do with guns but it’s still probably up your alley.

“The Thinking Man’s Guide to Hitting a Moose”

Ditto.

Merch

Top-quality hats, t-shirts, and patches.

OSD office hours

If you’re a new gun owner, thinking about becoming one, or know someone who is, come to OSD office hours. It’s a free 30-minute video call with an OSD team member to ask any and all your questions.

Support

Like what we’re doing? You can support us at the link below.