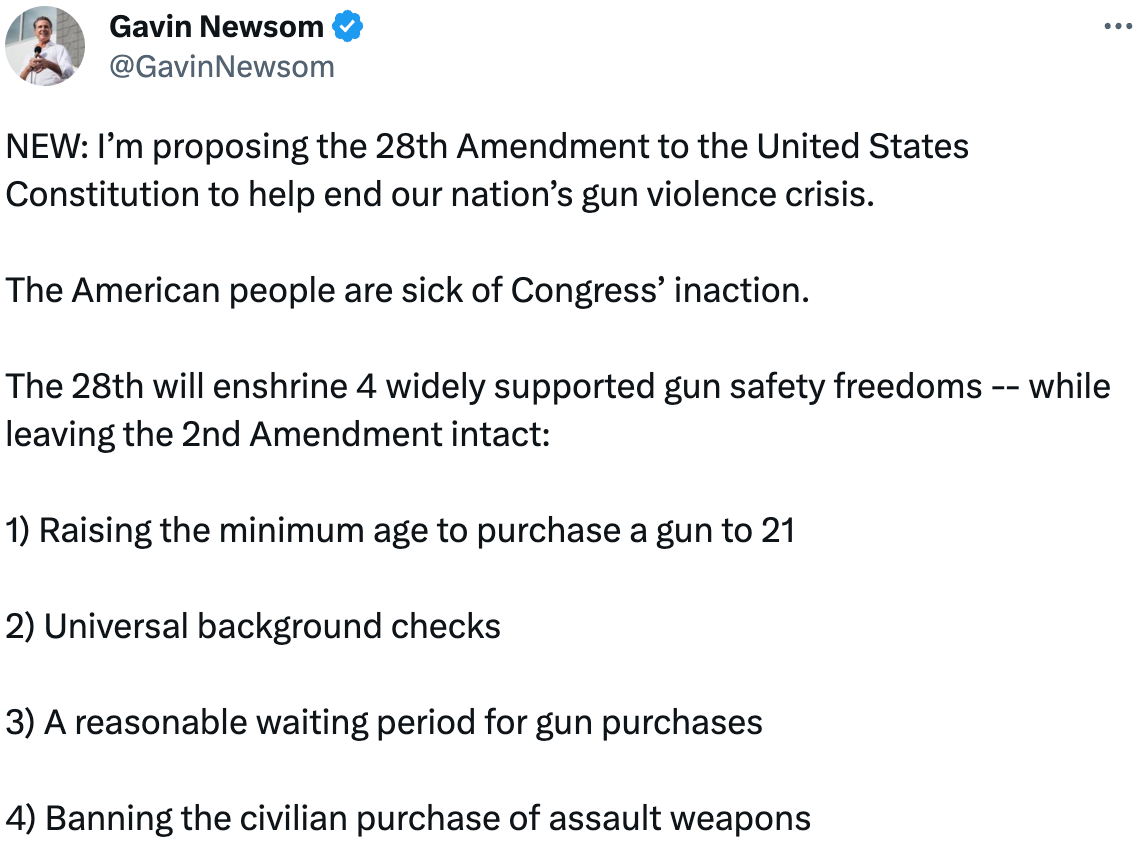

Gavin Newsom put this out a couple weeks ago:

We didn’t mention it at the time because it’s the kind of empty posturing that we usually ignore around here. It is useful for one thing, though. It’s a good lens into the underlying mindset that generates ideas like these.

Back in 1929, in The Thing: Why I Am a Catholic, G.K. Chesterton introduced a decision-making principle that came to be known as Chesterton’s fence:

In the matter of reforming things, as distinct from deforming them, there is one plain and simple principle; a principle which will probably be called a paradox. There exists in such a case a certain institution or law; let us say, for the sake of simplicity, a fence or gate erected across a road. The more modern type of reformer goes gaily up to it and says, “I don’t see the use of this; let us clear it away.” To which the more intelligent type of reformer will do well to answer: “If you don't see the use of it, I certainly won’t let you clear it away. Go away and think. Then, when you can come back and tell me that you do see the use of it, I may allow you to destroy it.”

This is often interpreted as a defense of conservatism in the Edmund Burke sense: evolve institutions gradually, don’t rip-and-replace, because they contain a lot of accumulated wisdom.

Chesterton’s point isn’t so hidebound. The parable of the fence isn’t an argument to fight progress, it’s an argument to seek knowledge. “Then, when you can come back and tell me that you do see the use of it, I may allow you to destroy it.” I.e. tear up the old stuff, but only once you know what you’re talking about. Essentially, Chesterton was warning about the Dunning-Kruger effect.

The case for gun rights is pretty simple: if someone’s trying to hurt you, you have the right to stop them. And by extension, you’re the person who’s in the best position to say how to stop them. We described it this way in OSD 117:

… the nature of gun ownership — the point of it, really — is that it decentralizes decision-making about self-defense. Who’s allowed to defend themselves, and how they should do so, becomes a loose emergent consensus rather than a top-down decision.

That’s the sort of illegible local knowledge that Chesterton warns would-be fence destroyers not to miss. The nature of top-down plans is to run roughshod over the actual needs and actual experience of the people closest to the ground. And not necessarily because that’s even the intent. It’s just a knowledge problem — even for an all-powerful, perfectly benevolent central decision-maker, there isn’t a way to gather all the local, on-the-ground facts to make the right decision. This is similar to part of Hayek’s argument for the price system in “The Use of Knowledge in Society” (bold emphasis added):

This is, perhaps, also the point where I should briefly mention the fact that the sort of knowledge with which I have been concerned is knowledge of the kind which by its nature cannot enter into statistics and therefore cannot be conveyed to any central authority in statistical form. The statistics which such a central authority would have to use would have to be arrived at precisely by abstracting from minor differences between the things, by lumping together, as resources of one kind, items which differ as regards location, quality, and other particulars, in a way which may be very significant for the specific decision. It follows from this that central planning based on statistical information by its nature cannot take direct account of these circumstances of time and place and that the central planner will have to find some way or other in which the decisions depending on them can be left to the “man on the spot.”

So it’s not that a gun control law even needs to deliberately tear down that people have a right to defend themselves. It’s that the law sees a fence in a field labeled “gun rights”, bulldozes it with good intentions to be replaced with a new fence called “gun control”, and lacks real knowledge of why the old fence performs better at safeguarding people’s ability to defend themselves.

There’s also the second-order problem that the bulldozer driver often doesn’t even understand how the new fence works or why they’re building it. Chesterton covered this, too, as excerpted by Farnam Street:

Suppose that a great commotion arises in the street about something, let us say a lamp-post, which many influential persons desire to pull down. A grey-clad monk, who is the spirit of the Middle Ages, is approached upon the matter, and begins to say, in the arid manner of the Schoolmen, “Let us first of all consider, my brethren, the value of Light. If Light be in itself good—”

At this point he is somewhat excusably knocked down. All the people make a rush for the lamp-post, the lamp-post is down in ten minutes, and they go about congratulating each other on their un-mediaeval practicality. But as things go on they do not work out so easily. Some people have pulled the lamp-post down because they wanted the electric light; some because they wanted old iron; some because they wanted darkness, because their deeds were evil. Some thought it not enough of a lamp-post, some too much; some acted because they wanted to smash municipal machinery; some because they wanted to smash something. And there is war in the night, no man knowing whom he strikes.

So, gradually and inevitably, to-day, to-morrow, or the next day, there comes back the conviction that the monk was right after all, and that all depends on what is the philosophy of Light. Only what we might have discussed under the gas-lamp, we now must discuss in the dark.

The tweet-length version of that would be “Are we the baddies?”

You see this dynamic play out in the gun control space frequently. Gun laws supported by well-intentioned but ill-informed do-gooders treat gun ownership as inherently suspect. That in turn leads to stop-and-frisk, pretextual stops, needlessly violent warrant execution, and overcriminalization — a suite of carceral state outcomes that the do-gooders wouldn’t have directly supported.

Gun rights people aren’t immune to this mistake either. The consumer market for steel armor — “who needs that expensive UHMWPE stuff anyway, steel is just as good” — is an example of hastily tearing down Chesterton’s fence. But the rise of, say, Holosun vs. Aimpoint is an example of thoughtfully tearing the fence down.

Another example: NYSRPA v. Bruen. Reading a draft of this essay, one of our Discord subscribers noted that to gun control groups, Bruen felt like a bulldozing of Chesterton’s fence. And yup, the law that de facto prohibited gun carry in New York City is 112 years old. So to people who didn’t know anything different, the right to carry a concealed handgun feels contrary to everything they know about where guns do and don’t belong. But remember, Chesterton’s admonition isn’t to never tear down a fence, it’s to only tear it down once you know the issue deeply. And between Bruen supporters and Bruen detractors, it’s the supporters who know more about the ins and outs of legal carry. (For example, it’s the supporters who are likelier to know that in 27 states, the status quo is already permitless carry.)

Sometimes there’s no good reason for things to stay the way they are. But sometimes there’s a great reason. Telling the two situations apart is often nearly impossible. If there’s to be any hope of making the right call, it’s found in rolling up your sleeves to engage with the details at an expert level. So seek knowledge, and be skeptical if someone needs to avoid knowledge in order to proceed with their plans for a fence.

This week’s links

A conversation with ChatGPT about teaching marksmanship at school…

…framed as an extension of the values that would also lead you to teach traditional martial arts. This was done by one of our characteristically clever Discord subscribers, who framed it like so:

I had an interesting conversation with ChatGPT on teaching traditional martial arts in schools, including marksmanship in America.

The big lesson I took away is that shifting the abstraction layer helps take the politics out of a conversation. Shifting it from “firearms in schools” to “cultural traditions and risk acceptance levels” led to some solid points.

1903 New York Times article about how it’s too easy to buy dynamite

“It’s one of the easiest things in the world to buy dynamite enough in this city to blow up half of lower Broadway, and the only wonder is that cranks and bad men and practical jokers do not furnish us with mere ‘scares’ like that of the infernal machine found on the Cunard piers,” said the manager of a big New York dynamite manufacturing company.

A few years later, there was a rash of politically-motivated bombings in the US — notably at a time when machine guns were for sale in mail-order catalogs. Perhaps a pre-modern example of violent social contagions akin to mass shootings today.

David Yamane reviews “Merchants of the Right: Gun Sellers and the Crisis of American Democracy”

A new book by sociologist Jennifer Carlson. The beginning of the review:

Judging from the regular inquiries I receive from international media, a robust civilian gun culture is enigmatic outside the United States. Or at least the particular civilian gun culture of the United States is. As the interdisciplinary study of guns shows, it is enigmatic to many Americans as well.

Smarter Every Day: bullets hitting each other in ultra slow-motion

This gets particularly cool at the 22-minute mark. Destin is a great ambassador for gun stuff.

Ammo Squared: “Pioneers get the arrows”

Essay from Ammo Squared about kneejerk skepticism in the gun community. This community, like most niches, has its share of people stuck in the “No wireless. Less space than a Nomad. Lame.” mentality when they see something new. (There was a good discussion of this in our Discord, too.)

New things come out. Some of them will work, some won’t. The important thing is that new things come out. That should be celebrated for its own sake. From “OSD 119: I’m not a LARPer, I’m just ahead of the curve”:

We think of LARPing as being defined by the gear someone’s using. In reality, it’s defined by the calendar. In the ‘70s, rocking an Aimpoint or a flashlight would have been LARPing. In the ‘60s, firing a pistol two-handed was LARPing. In the ‘20s, a semi-auto rifle was LARPing.

Choose any point in time, and it turns out that the LARPers were actually something different: early adopters. Why would today be any different? Of course, some trends are going to seem silly in hindsight. The 10mm and visible laser aiming devices didn’t pan out either. But that’s a feature, not a bug. It’s how innovation works. New stuff comes out all the time, and early adopters try everything to figure out what’s good. Then the rest of us pile onto the good stuff. The process doesn’t work without early adopters — without LARPers — because by definition, you don’t know ahead of time what’s good and what’s not. At the beginning, it all looks silly. So if you want to create anything new, you need people who don’t mind looking silly.

Light switch cover plates shaped like little USPSA targets

Dry fire rules.

OSD Discord server

If you like this newsletter and want to talk live with the people behind it, join the Discord server. The OSD team and readers are there. Good vibes only. Plus monthly movie watch parties.

Merch

Gun apparel you’ll want to wear out of the house.

Office hours

If you’re a new gun owner, thinking about becoming one, or know someone who is, come to OSD office hours. It’s a free 30-minute video call with an OSD team member to ask any and all your questions.

I am consistently impressed with the quality of the writing from Open Source Defense.

It is eloquent, substantive, and about a topic close to my heart.

I'm strongly considering printing out these articles to add them to a binder, so that I can share them with future generations.

"will enshrine 4 widely supported gun safety freedoms"

Lists 4 restrictions.

1984 wasn't a how-to manual.