OSD 241: Violence is like getting into Harvard

The risks are here, they’re just not evenly distributed.

The term “gun deaths” is effective marketing. It sweeps in murders done with a gun, suicides done with a gun, and accidental shooting deaths; lumps them all into a single category so that they seem to have the same cause; and deftly implies that that cause is high gun ownership rates. Pretty impressive for two words.

Here’s a typical example of how that can be used to launder cultural preferences into something that sounds like a real data-driven insight:

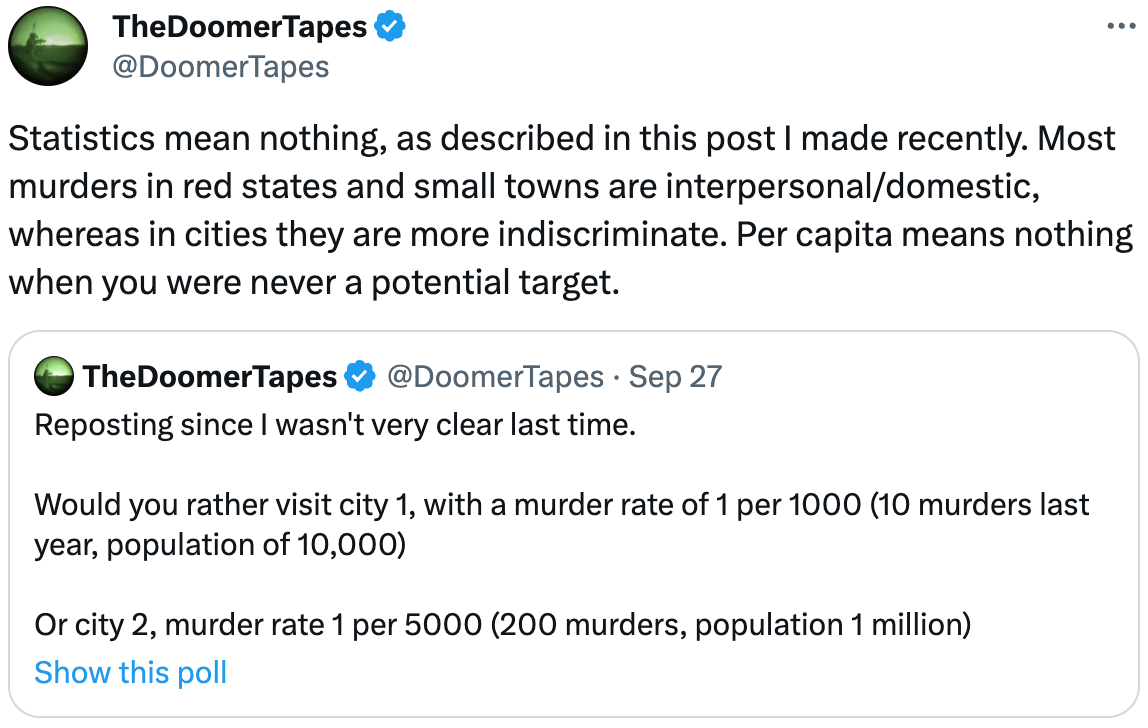

“Person contorts data to suit his agenda” is not exactly a news story. But in the replies, somebody made a broader claim:

“Statistics mean nothing”, now that’s a news story.

Take California’s 2021 murder rate of 6.4 murders per 100,000 people. That means that in 2021, 0.0064% of the people in California were murdered. A naive interpretation is that for each year you spend in California, you have a 0.0064% chance — 1 in 15,625 — of being murdered.

But that assumes the risk is evenly distributed, and of course it is not. Statistics change based on how far you zoom in. This is an example of Simpson’s paradox. An easy way to demonstrate it is to zoom out as far as possible. The worldwide average homicide rate is roughly 6.1 murders per 100,000 people. But that doesn’t tell you anything about your own personal murder risk. You can keep going and make it even more useless — zoom out further to the whole universe, whose murder rate asymptotically approaches zero. Equally useless for telling you whether you should walk outside alone at night.

This applies to any process where you try to translate group-level outcomes into your own personal odds for seeing the same outcome. A story from memory (because Google isn’t turning it up): Paul Graham was talking about Y Combinator acceptance rates on a forum once, 10+ years ago. He said something to the effect of, “Y Combinator having a 2% acceptance rate doesn't mean that you have a 2% chance of getting in. It means that 2% of applicants have a near-100% chance, and 98% of applicants have almost zero chance.”

(Please reach out if you’re able to find a link for the anecdote above.)

Another example: diseases. The paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould was diagnosed with mesothelioma in 1982. He described it in an essay called “The Median Isn’t the Message”:

In July 1982, I learned that I was suffering from abdominal mesothelioma, a rare and serious cancer usually associated with exposure to asbestos. When I revived after surgery, I asked my first question of my doctor and chemotherapist: “What is the best technical literature about mesothelioma?” She replied, with a touch of diplomacy (the only departure she has ever made from direct frankness), that the medical literature contained nothing really worth reading.

Of course, trying to keep an intellectual away from literature works about as well as recommending chastity to Homo sapiens, the sexiest primate of all. As soon as I could walk, I made a beeline for Harvard’s Countway medical library and punched mesothelioma into the computer’s bibliographic search program. An hour later, surrounded by the latest literature on abdominal mesothelioma, I realized with a gulp why my doctor had offered that humane advice. The literature couldn’t have been more brutally clear: Mesothelioma is incurable, with a median mortality of only eight months after discovery. I sat stunned for about fifteen minutes, then smiled and said to myself: So that’s why they didn’t give me anything to read. Then my mind started to work again, thank goodness.

…

The problem may be briefly stated: What does “median mortality of eight months” signify in our vernacular? I suspect that most people, without training in statistics, would read such a statement as “I will probably be dead in eight months”—the very conclusion that must be avoided, both because this formulation is false, and because attitude matters so much.

I was not, of course, overjoyed, but I didn’t read the statement in this vernacular way either. My technical training enjoined a different perspective on “eight months median mortality.” The point may seem subtle, but the consequences can be profound. Moreover, this perspective embodies the distinctive way of thinking in my own field of evolutionary biology and natural history.

…

When I learned about the eight-month median, my first intellectual reaction was: Fine, half the people will live longer; now what are my chances of being in that half? I read for a furious and nervous hour and concluded, with relief: damned good. I possessed every one of the characteristics conferring a probability of longer life: I was young; my disease had been recognized in a relatively early stage; I would receive the nation’s best medical treatment; I had the world to live for; I knew how to read the data properly and not despair.

Another technical point then added even more solace. I immediately recognized that the distribution of variation about the eight-month median would almost surely be what statisticians call “right skewed.” (In a symmetrical distribution, the profile of variation to the left of the central tendency is a mirror image of variation to the right. Skewed distributions are asymmetrical, with variation stretching out more in one direction than the other—left skewed if extended to the left, right skewed if stretched out to the right.) The distribution of variation had to be right skewed, I reasoned. After all, the left of the distribution contains an irrevocable lower boundary of zero (since mesothelioma can only be identified at death or before). Thus, little space exists for the distribution’s lower (or left) half—it must be scrunched up between zero and eight months. But the upper (or right) half can extend out for years and years, even if nobody ultimately survives. The distribution must be right skewed, and I needed to know how long the extended tail ran—for I had already concluded that my favorable profile made me a good candidate for the right half of the curve.

Gould eventually died in 2002 of an unrelated cancer (and ironically had the opposite experience the second time around, passing away ten weeks after diagnosis).

This misapplication of group-level statistics drives a lot of false ideas. Especially around violence. When you hear about St. Louis or Baltimore being dangerous cities, what you’re actually hearing is that you need to zoom in. In most parts of those cities, your risk of being murdered is effectively zero. Then there are a handful of neighborhoods where murder rates are many times higher than the already-very-high city-wide number, and those neighborhoods pull the average up.

Group-level stats vs. individual stats also explains the cultural reaction to mass shootings, a vanishingly unlikely cause of death. But that is violence that randomly targets people who in all other respects have managed their risk of murder down to effectively zero, so it would be surprising if they didn’t react strongly.

That overreaction is also a sign of something good though. It means that people sometimes have an intuitive sense for how group-level statistics don’t apply to them. Even though people “shouldn’t” worry about mass shootings, if they intuit that their personal risk of murder is ~zero, they’ll respond against anything that worsens their odds, no matter how slightly.

Risk management is a good impulse, and ironically it’s also the impulse that drives much of gun culture. So the way to redirect that energy is towards helping people build an internal locus of control. They want to manage their individual-level risks. Great! Welcome to gun culture.

This week’s links

“I called for the emergency destruct plan“

Many of you may be thinking how horrible this must have been. Thousands of miles from home, two and a half miles up in space, your aircraft damaged to an unknown extent, cabin decompressed, spinning out of control, 24 lives in your hands, as well as the possible welfare of your homeland. The pucker factor was high, 10 out of ten. You most likely couldn't have pulled a pencil out of the pilot's ass with a pair of linesman's pliers. He was terrified. He was also wrapped inside his own little version of heaven.

Let me explain.

Federal judge blocks much of Maryland’s “sensitive places” law

From The Reload.

MOAB

OSD Discord server

If you like this newsletter and want to talk live with the people behind it, join the Discord server. The OSD team and readers are there. Good vibes only.

Merch

Gun apparel you’ll want to wear out of the house.

" if they intuit that their personal risk of murder is ~zero, they’ll respond against anything that worsens their odds, no matter how slightly. "

I think we've just come onto the reason why people react to mass shootings the way they do. It's disruptive to their sense of risk. They know they're generally immune to 'normal' murder, but the mass shooter, rare as it is, disrupts the algebra. This experience is inherently disconcerting.

> But that assumes the risk is evenly distributed, and of course it is not. Statistics change based on how far you zoom in. This is an example of Simpson’s paradox. An easy way to demonstrate it is to zoom out as far as possible. The worldwide average homicide rate is roughly 6.1 murders per 100,000 people. But that doesn’t tell you anything about your own personal murder risk. You can keep going and make it even more useless — zoom out further to the whole universe, whose murder rate asymptotically approaches zero. Equally useless for telling you whether you should walk outside alone at night.

This is one of my Big Ideas, and I'm sure I've shared it here before.

ALL statistics about "The United States" are meaningless, because they are statistical aggregates over a highly heterogenous population that do not generalize to any individuals in that population

So, to make up some illustrative numbers, you might hear that the murder rate in the US is 10/100k. So you might think, I have a one in ten thousand chance, per year, of being murdered.

Except, inevitably, the way they got that 10/100k murder rate was by averaging over a bunch of sleepy quiet areas where the murder rate is essentially 0, and then a bunch of violent inner city neighbourhoods where the murder rate is 200/100k. The average is technically correct, but meaningless if your goal is to evaluate your own personal risk of being murdered.

This is true of _**ALL**_ stats in the US, on all subjects, always. You have to drill down and be way more specific and targetted in your statistical analysis before the output becomes useful