OSD 278: Bump stocks are legal again. Does that matter?

Breaking down the Supreme Court's ruling in Garland v. Cargill.

On Friday the Supreme Court struck down the ATF’s bump stock ban. Let’s break down the justices’ opinions and the implications.

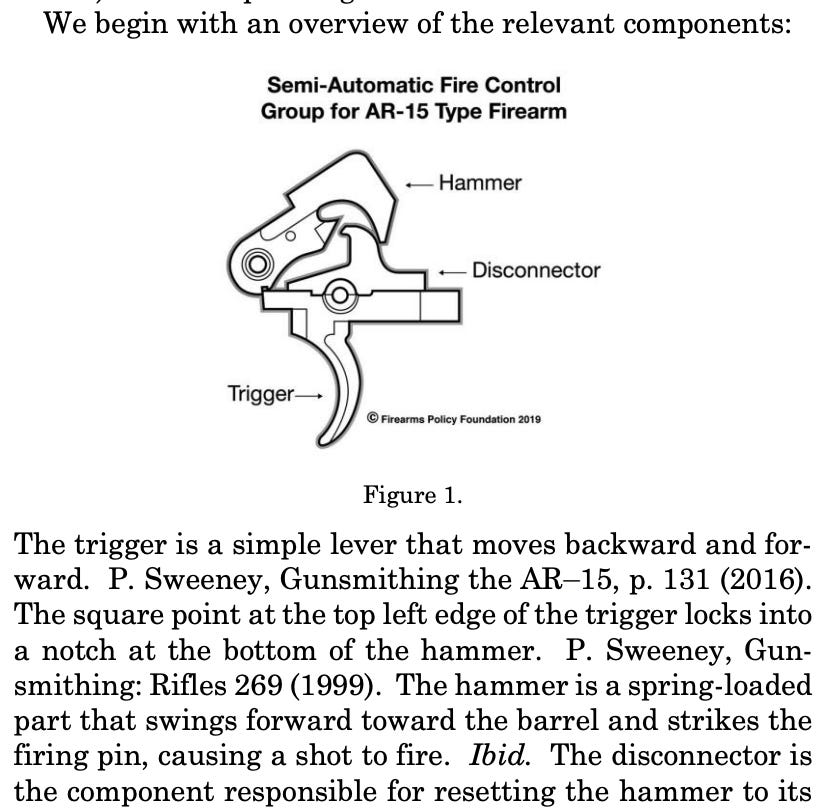

Clarence Thomas writes for a 6-3 majority, and the overriding theme of his opinion is that this is not a hard case. Under the NFA, a machine gun is “any weapon which shoots, is designed to shoot, or can be readily restored to shoot, automatically more than one shot, without manual reloading, by a single function of the trigger”. Bump stocks are simply not that. That’s obvious if and only if you know how a bump stock works. Thomas explains that by explaining how an AR-15’s fire control group works.

No one disputes that a semiautomatic rifle without a bump stock is not a machinegun because it fires only one shot per “function of the trigger.” That is, engaging the trigger a single time will cause the firing mechanism to discharge only one shot. To understand why, it is helpful to consider the mechanics of the firing cycle for a semiautomatic rifle. Because the statutory definition is keyed to a “function of the trigger,” only the trigger assembly is relevant for our purposes. Although trigger assemblies for semiautomatic rifles vary, the basic mechanics are generally the same. The following series of illustrations depicts how the trigger assembly on an AR–15 style semiautomatic rifle works. In each illustration, the front of the rifle (i.e., the barrel) would be pointing to the left.

He then uses diagrams from FPC’s amicus brief to explain:

Gun design lesson concluded, he brings it home:

ATF does not dispute that this complete process is what constitutes a “single function of the trigger.” A shooter may fire the weapon again after the trigger has reset, but only by engaging the trigger a second time and thereby initiating a new firing cycle. For each shot, the shooter must engage the trigger and then release the trigger to allow it to reset. Any additional shot fired after one cycle is the result of a separate and distinct “function of the trigger.”

Nothing changes when a semiautomatic rifle is equipped with a bump stock. The firing cycle remains the same. Between every shot, the shooter must release pressure from the trigger and allow it to reset before reengaging the trigger for another shot. A bump stock merely reduces the amount of time that elapses between separate “functions” of the trigger. The bump stock makes it easier for the shooter to move the firearm back toward his shoulder and thereby release pressure from the trigger and reset it. And, it helps the shooter press the trigger against his finger very quickly thereafter. A bump stock does not convert a semiautomatic rifle into a machinegun any more than a shooter with a lightning-fast trigger finger does. Even with a bump stock, a semiautomatic rifle will fire only one shot for every “function of the trigger.” So, a bump stock cannot qualify as a machinegun under §5845(b)’s definition.

At that point the case is basically over. The ATF’s argument had been that a bump stock does work with a single function of the trigger. Their pitch is that the initial trigger pull plus the continuous forward pressure from the shooter’s support arm constitute “a single function” that swallows up all the subsequent shots. Oral arguments in the case are worth a listen, because Principal Deputy Solicitor General Brian Fletcher is an impressive advocate and sounds pretty persuasive making that argument. But in the majority opinion, Thomas firmly closes the door on it:

Although ATF agrees on a semiautomatic rifle’s mechanics, it nevertheless insists that a bump stock allows a semiautomatic rifle to fire multiple shots “by a single function of the trigger.” ATF starts by interpreting the phrase “single function of the trigger” to mean “a single pull of the trigger and analogous motions.” A shooter using a bump stock, it asserts, must pull the trigger only one time to initiate a bump-firing sequence of multiple shots. This initial trigger pull sets off a sequence—fire, recoil, bump, fire—that allows the weapon to continue firing “without additional physical manipulation of the trigger by the shooter.” According to ATF, all the shooter must do is keep his trigger finger stationary on the bump stock’s ledge and maintain constant forward pressure on the front grip to continue firing. The dissent offers similar reasoning.

This argument rests on the mistaken premise that there is a difference between a shooter flexing his finger to pull the trigger and a shooter pushing the firearm forward to bump the trigger against his stationary finger. ATF and the dissent seek to call the shooter’s initial trigger pull a “function of the trigger” while ignoring the subsequent “bumps” of the shooter’s finger against the trigger before every additional shot. But, §5845(b) does not define a machinegun based on what type of human input engages the trigger—whether it be a pull, bump, or something else. Nor does it define a machinegun based on whether the shooter has assistance engaging the trigger. The statutory definition instead hinges on how many shots discharge when the shooter engages the trigger. And, as we have explained, a semiautomatic rifle will fire only one shot each time the shooter engages the trigger—with or without a bump stock.

In any event, ATF’s argument cannot succeed on its own terms. The final Rule defines “function of the trigger” to include not only “a single pull of the trigger” but also any “analogous motions.” ATF concedes that one such analogous motion that qualifies as a single function of the trigger is “sliding the rifle forward” to bump the trigger. But, if that is true, then every bump is a separate “function of the trigger,” and semiautomatic rifles equipped with bump stocks are therefore not machineguns. ATF resists the natural implication of its reasoning, insisting that the bumping motion is a “function of the trigger” only when it initiates, but not when it continues, a firing sequence. But, Congress did not write a statutory definition of “machinegun” keyed to when a firing sequence begins and ends. Section 5845(b) asks only whether a weapon fires more than one shot “by a single function of the trigger.”

That’s the gist of the majority opinion. Let’s move on to Alito’s concurrence. It reads, in full:

I join the opinion of the Court because there is simply no other way to read the statutory language. There can be little doubt that the Congress that enacted 26 U.S.C. §5845(b) would not have seen any material difference between a machinegun and a semiautomatic rifle equipped with a bump stock. But the statutory text is clear, and we must follow it.

The horrible shooting spree in Las Vegas in 2017 did not change the statutory text or its meaning. That event demonstrated that a semiautomatic rifle with a bump stock can have the same lethal effect as a machinegun, and it thus strengthened the case for amending §5845(b). But an event that highlights the need to amend a law does not itself change the law’s meaning.

There is a simple remedy for the disparate treatment of bump stocks and machineguns. Congress can amend the law—and perhaps would have done so already if ATF had stuck with its earlier interpretation. Now that the situation is clear, Congress can act.

We’ll come back to that, but keep it in the back of your mind.

Now the dissent. Sonia Sotomayor writes for a three-justice minority. This passage captures the crux of her argument:

When a shooter initiates the firing sequence on a bumpstock-equipped semiautomatic rifle, he does so with “a single function of the trigger” under that term’s ordinary meaning. Just as the shooter of an M16 need only pull the trigger and maintain backward pressure (on the trigger), a shooter of a bump-stock equipped AR-15 need only pull the trigger and maintain forward pressure (on the gun). Both shooters pull the trigger only once to fire multiple shots. The only difference is that for an M16, the shooter’s backward pressure makes the rifle fire continuously because of an internal mechanism: The curved lever of the trigger does not move. In a bump-stock-equipped AR–15, the mechanism for continuous fire is external: The shooter’s forward pressure moves the curved lever back and forth against his stationary trigger finger. Both rifles require only one initial action (that is, one “single function of the trigger”) from the shooter combined with continuous pressure to activate continuous fire.

“[P]ull the trigger only once to fire multiple shots” is not how bump stocks work. The later parts of the paragraph try to distinguish the first trigger pull from the subsequent ones on the premise that after the first one, all the trigger pulls are caused by the continuous forward pressure from the shooter’s support hand. So, the pitch goes, it’s really all one big trigger pull. But there’s no getting around the fact that they are individual, manual trigger pulls — separate functions of the trigger — no matter how they’re happening.

So why are Sotomayor making an obviously incorrect argument about the facts here?

Well, Section C captures the true spirit of the dissent. It begins:

This Court has repeatedly avoided interpretations of a statute that would facilitate its ready “evasion” or “enable offenders to elude its provisions in the most easy manner.” Justice Scalia called this interpretive principle the “presumption against ineffectiveness.” The majority arrogates Congress’s policymaking role to itself by allowing bumpstock users to circumvent Congress’s ban on weapons that shoot rapidly via a single action of the shooter.

Antonin Scalia once described the presumption against ineffectiveness as “the idea that Congress presumably does not enact useless laws”. One imagines he chuckled sarcastically while writing that. But the point is that courts should not interpret a law in a way that nullifies the law’s goal. In this case, Sotomayor uses that to suggest that courts should read this law to mean anything necessary to achieve the presumed goal, even if it violates the plain text of the law. She explains:

The majority tosses aside the presumption against ineffectiveness, claiming that its interpretation only “draws a line more narrowly than one of [Congress’s] conceivable statutory purposes might suggest” because the statute still regulates “all traditional machineguns” like M16s. Congress’s ban on M16s, however, is far less effective if a shooter can instead purchase a bump stock or construct a device that enables his AR-15 to fire at the same rate. Even bump-stock manufacturers recognize that they are exploiting a loophole, with one bragging on its website “Bumpfire Stocks are the closest you can get to full auto and still be legal.”

Gun companies back at it again with their dastardly tactics of complying with the law.

This is of course really what the case was about. For people who want the machine gun ban to be a rate of fire ban, this was about whether that goal is worth allowing federal agencies to simply make up their own laws. You’d think that people would consider how a president they don’t like would use that power. But in these matters people aren’t incentivized to think about the long-term. They’re incentivized to score points today, consequences be damned.

There are a lot of political incentives for a rate of fire ban. Hoffnung, a user on our Discord, pointed out that there was a trend towards such bans after the Las Vegas music festival shooting. California had banned bump stocks since 1990, but D.C., Delaware, Florida, Hawaii, Maryland, Massachusetts, Nevada, New Jersey, New York, and Washington banned them after the shooting. Several states banned crank triggers too, and binary triggers are illegal in New Jersey. In 2022, the ATF issued an open letter saying that they’re going to treat some forced-reset triggers as machine guns. That’s a lot of social pressure to hold back with just a simple insistence on sticking to the text of the law. It’s good that the Supreme Court held their ground here.

But this case also showed the limits of where the Supreme Court is going to go on the Second Amendment. Even the justices in the majority went out of their way during oral arguments to say, essentially, that they’d agree to an act of Congress banning bump stocks, and Alito went further with his concurrence — a sitting justice openly calling for Congress to pass a specific law. That’s abnormal.

The next test is the Rahimi case, for which the Supreme Court will release its ruling sometime in the next two weeks. (The next possible date is this Thursday.) That case is about someone who was charged with possessing a gun while under a domestic violence restraining order, and it might change the shape of the law around prohibited persons. Based on Garland v. Cargill, we shouldn’t expect the Court to make huge waves here. They might keep the law as-is, or they might issue a ruling laying out some principles, saying Rahimi’s as-applied challenge fails (i.e. he doesn’t get off the hook — he is by all accounts a violent criminal), and telling future defendants to work out the details in their own cases.

The bigger test will be the cases coming through the system on assault weapon bans, magazine bans, and the Bruen response laws in California and New York. We’ve been hoping those build towards an eventual case that strikes down the NFA. We have a clear signal now that that’s not going to happen with respect to machine guns. Whether it happens with respect to silencers and SBRs will depend on these upcoming cases. The NFA is essentially a federal licensing scheme similar to (and in fact lighter than) what New York City requires from its legal gun owners. If the status quo in New York survives the Court’s review, then it’s hard to see how the NFA wouldn’t. We’ll find out soon.

This week’s links

Previous newsletter about the pistol brace ban, another example of ATF pushing the limit of its rulemaking powers

More about Open Source Defense

Merch

Grab a t-shirt or a sticker.

OSD Discord server

If you like this newsletter and want to talk live with the people behind it, join the Discord server. The OSD team is there along with tons of readers.

If the minority had the votes on SCOTUS, that would make SCOTUS the third branch of the Legislature. And that IS what the Left wants. "Only slaves need permission"--SGH