The Supreme Court released their opinion in Rahimi on Friday and reactions ranged from sanguine:

to unaffected:

to whatever is going on here:

Robert Leider’s view above is the consensus across most people — that the Court decided that Rahimi wasn’t entitled to a gun while under his domestic violence restraining order and … that’s about it.

In a concurrence, Neil Gorsuch went out of his way to be very clear about what the Court didn’t decide:

Whether it's constitutional to disarm someone without a judicial finding that they pose a credible threat

Whether permanent disarmament is constitutional at all, and if so, in which cases

Whether disarmament laws are enforceable in cases where someone uses a gun in self-defense

Whether disarmed individuals must be allowed to apply for exceptions, similar to a may-issue process

Whether disarmament of entire categories of people is constitutional

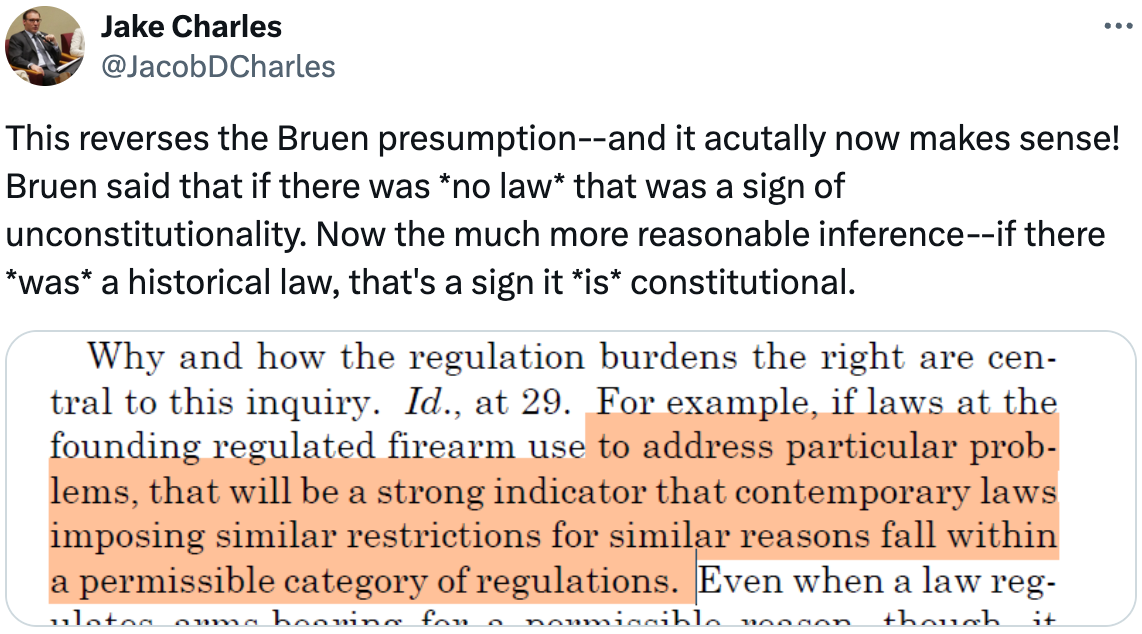

So in practice, nothing substantial changed. There are some tea leaves to read, but that’s all. No clear takeaways. John Roberts in the 8-1 majority opinion did try to clarify the Bruen test, as explained below by Stephen Gutowski at The Reload:

The more substantial outcome of the ruling is found in how it got to the conclusion the modern ban was constitutional and the message it sent to the lower courts.

“[S]ome courts have misunderstood the methodology of our recent Second Amendment cases. These precedents were not meant to suggest a law trapped in amber,” Chief Justice John Roberts wrote for the majority. “As we explained in Heller, for example, the reach of the Second Amendment is not limited only to those arms that were in existence at the founding. Rather, it ‘extends, prima facie, to all instruments that constitute bearable arms, even those that were not [yet] in existence.’ By that same logic, the Second Amendment permits more than just those regulations identical to ones that could be found in 1791. Holding otherwise would be as mistaken as applying the protections of the right only to muskets and sabers.”

The opinion was primarily a rebuke of the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals for the way it applied Bruen, which the majority reminded everyone it did not mean to be a regulatory “straightjacket.”

“For its part, the Fifth Circuit made two errors,” Roberts wrote. “First, like the dissent, it read Bruen to require a ‘historical twin’ rather than a ‘historical analogue.’ Second, it did not correctly apply our precedents governing facial challenges.”

You could catastrophize that if you want, under the concern that it’ll give lower courts license to contort Bruen out of existence. But what were lower courts doing before? As @fourboxesdiner and @2Aupdates point out:

Gorsuch mentioned this too:

Just consider how lower courts approached the Second Amendment before our decision in Bruen. They reviewed firearm regulations under a two-step test that quickly “devolved” into an interest-balancing inquiry, where courts would weigh a law’s burden on the right against the benefits the law offered. Some judges expressed concern that the prevailing two-step test had become “just window dressing for judicial policymaking.” To them, the inquiry worked as a “black box regime” that gave a judge broad license to support policies he “[f]avored” and discard those he disliked. How did the government fare under that regime? In one circuit, it had an “undefeated, 50–0 record.” In Bruen, we rejected that approach for one guided by constitutional text and history. Perhaps judges’ jobs would be easier if they could simply strike the policy balance they prefer. And a principle that the government always wins surely would be simple for judges to implement. But either approach would let judges stray far from the Constitution’s promise.

Lower courts will absolutely use Rahimi to narrow Bruen from below. But that’s nothing new. It’s the same thing they’ve been doing since Heller. Gutowski even points out a post-Bruen case where a First Circuit panel upheld a magazine ban by finding historic laws whose goal — a generic interest in public safety — matched the mag ban’s stated goals. A far cry from Bruen’s test.

“The justification for the law is a public safety concern comparable to the concerns justifying the historical regulation of gunpowder storage and of weapons like sawed-off shotguns, Bowie knives, M-16s and the like,” Judge William Kayatta, a Barack Obama appointee, wrote in Ocean State Tactical v. Rhode Island. “The analogical ‘how’ and ‘why’ inquiry that Bruen calls for therefore strongly points in the direction of finding that Rhode Island’s [ban on magazines holding more than 10 rounds] does not violate the Second Amendment.”

The thing that would stop that is a SCOTUS ruling that (a) makes the text, history, and tradition test clearer for lower courts and (b) demonstrates the test by striking down a substantial existing gun law. Rahimi was never going to be that case. We wrote this up last year in:

Here’s the relevant part:

Rahimi is an unsympathetic defendant — all indications are that he’s a violent criminal. In law there’s an idea called “bad facts”. That’s when a case might have some academically interesting angle to it which may or may not be correct, but then you can’t even reach that question because the case is dominated by some ugly or inconvenient facts. It doesn’t even have to be an unsympathetic defendant. It could just be that the case has a complex procedural history, standing issues, or a million other things. Anything that distracts from the core question.

Conversely, you could have “good facts”. Sometimes those cases are even deliberately engineered. The original DC v. Heller case was engineered, with Dick Heller hand-picked by the Cato Institute from the very beginning. Rosa Parks’s protest was not engineered, but after her arrest the NAACP saw that her case teed up the core question of bus segregation nicely and they put their institutional muscle behind her.

Rahimi is … not Rosa Parks. And while he may be right that 922(g)(8) needs an update, it’s a lot simpler to just have tidy, sympathetic cases in the first place. There’s even an idea that it might be smarter to strategically moot Rahimi’s case in order to avoid a Supreme Court ruling that’s skewed by the bad facts here.

So as a case to set precedent, Rahimi did absolutely nothing in any direction. That’s good, because every other realistic outcome would have been worse.

The best predictor of what happens next is what SCOTUS does with the cases coming up through the system. @2Aupdates’ tracker has cases awaiting cert decisions on assault weapons bans, Bruen response laws, and prohibited persons. A Paul Clement mag ban case (the Rhode Island one mentioned above, now called Ocean State Tactical v. Neronha) is about to petition for cert. These are big cases. If the Court takes up 1+ of them, we’ll have more substantive 2A precedent by July 2025. In the best case scenario, that means the end of AWBs or mag bans. But if SCOTUS denies cert on all the cases, that’s a clear signal that this Court has said all it’s going to say on 2A.

If that happens, we’ve faced it before. Way back in:

All the progress we’ve made as a community — the CCW tidal wave; the AR-15’s ascent into ubiquity; the long-term polling shifting towards gun rights, especially among young people — that has all been done with essentially zero help from the courts. So the job today is the same as it was yesterday: keep the work going. Make more gun owners. Train them up. Build the community. Be cool and friendly. If this whole community keeps working on that like it has been for the past 10+ years, we’re going to get the results that we all want to see.

The linked article in that excerpt is due for an update, but the gist remains true. Keep building. If SCOTUS helps out, that’s great. But if they don’t, the answer is to keep building anyway.

This week’s links

T.Rex Labs: “What the next generation of duty pistols will be like”

Speaking of building, check this out from Isaac Botkin, the Lucius Fox of guntube.

Thread on drones. Heavy military hardware is obsolete, it just doesn’t know it yet.

Imagine AI doing most of the work of identifying and locating a target, then phoning home to a drone operator to pull the trigger. Drone operators will shift away from “flying” drones and locating targets, and instead will be preoccupied with switching to various drone screens on ready to attack targets dozens of time throughout the day.

We covered a similar theme in:

Thread on why forced-entry police raids are incompatible with gun rights

Familiar pattern: someone defends their house against home invaders and then gets killed because the home invaders turned out to be police.

NYT: “The Gun Lobby’s Hidden Hand in the 2nd Amendment Battle”

This piece blows the lid off the story of … an expert in something being a paid expert witness. But it does have this interesting scoop from SCOTUS’s Bruen deliberations:

The draft opinion that Justice Clarence Thomas circulated to his colleagues in February 2022 was sweeping, with the potential to outlaw many common gun-control measures. The majority was slow to sign on. Chief Justice John Roberts and Justice Kavanaugh requested modifications, according to people familiar with the deliberations, who requested anonymity because that process is intended to be secret.

By May, Justice Thomas still had not mustered the five votes needed. Mass shootings that month in Buffalo and Uvalde galvanized public attention anew on gun violence. It was not until June that his opinion prevailed, when Justice Kavanaugh signed on but wrote his own more moderate concurrence, joined by the chief.

More about Open Source Defense

Merch

Grab a t-shirt or a sticker.

OSD Discord server

If you like this newsletter and want to talk live with the people behind it, join the Discord server. The OSD team is there along with tons of readers.